Welcome to Fearful Franchise: a series of essays about franchise horror films running daily throughout October. This year we’re focusing on the Universal Monster Movies.

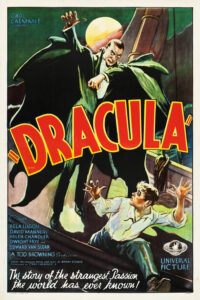

We kick off this year’s Fearful Franchise with Tod Browning’s Dracula, a film that is remarkable for all the things it set in motion. Not only did it give us Bela Lugosi as Dracula, a performance that became the standard for the character, it also set the Universal Monster series in motion and established the aesthetics of Halloween horror. On top of all that, the movie is a text ripe for analysis since it, just like the book, portrays anxieties over immigration, purity, and sexuality. However, despite all the interesting discussions that can be had around the movie, it’s remarkably dull.

Dracula is, of course, an adaptation of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel, but specifically an adaptation of a stage play of Dracula. So not only is the movie an adaptation of an adaptation, it’s an adaptation of a version that, by necessity, would be pretty static and talky. We could blame the movie’s origins for how dull and visually uninteresting it is, however there is a Spanish version of the movie shot at the same time on the same sets using a translation of the same script that is not only sprightly and visually arresting, it’s half-an-hour longer while feeling remarkably shorter. I’ll talk more about that tomorrow, though.

To offer a very brief summary, the novel Dracula details Count Dracula’s arrival in London through the letters and diaries of a band of heroes who eventually realize he’s a vampire and kill him. The movie tells the same story in a slightly condensed form. The novel has a bit more of Dracula preparing to move to London, a bit of hunting for his boxes of earth stashed all over the city, and a few more characters to round things out. One thing the movie and book have in common is that the only interesting part is the beginning at Dracula’s castle. In the novel, Johnathan Harker has traveled there to present the Count with real estate papers for Carfax Abbey in London. In the movie, it’s Renfield. In both cases, this is where there’s actual drama and threat and where the spookiness is allowed off the leash.

Which brings me to my first point: the aesthetics. The beginning of the movie has Renfield riding the horse-drawn carriage first to a small town and then up to Borgo Pass where he’s picked up by Dracula’s carriage. We have the small European village that feels anachronistic, positively medieval, and then the wonder of Dracula’s castle, all spacious and cobwebbed and dilapidated. The room is dominated by a massive staircase that curves off out of frame. The whole impression is of a building that defies space, that defies time, and stretches off into mystery in every direction.

And we kind of stuck with that for horror movies from then on. Nearly all the Universal movies I’ll be covering here share that aesthetic, but it’s also the look, although awash in lurid colors, of the Hammer Horror films that build upon the Universal Monsters as well as Roger Corman’s stab at the gothic in his adaptations of Edgar Allen Poe. More than that, the horror host shows of the 60’s (which are a big part of why the Universal Monsters are the “Universal Monsters”) latched onto that look and it’s become the standard for horror host shows ever since. While horror has become a vast and diverse genre, the starkly lit castle perched on a cliffside with lightning in the background is shorthand for horror. Even children’s cartoons—media intended for an audience without any of this context—uses the images originated here as indicators of spookery.

Another striking aspect of the first act of the movie is Dwight Frye as Renfield. Lugosi, of course, is iconic as Dracula, but he’s not allowed to be the full, villainous, scenery-chewing version until Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein. His role, in fact, is pretty small. Dracula is talked about being a menace more than he is actually menacing people on screen. Instead, we have a lot of boring upper-middle-class people lounging on chairs talking about the potential for dreadful things to happen. In this, the movie is extremely faithful to the book.

However, Frye stands out. He gives a performance that turns from naïve to manic to repentant to exultant. Renfield is supposed to be mentally disturbed after his encounter with Dracula, and Frye delivers. He goes big which is what this movie needs.

What’s also interesting about his performance is the queerness of it. He comes across as a spurned lover desperate to be taken back. If you wanted to imagine the story as a society drama instead of a horror film, Dracula seduces Renfield then drops him once they arrive in London. Dracula tries to solidify his place in society by pursuing women, but Renfield’s ardor keeps threatening to reveal their previous liaison. In the end, Renfield’s efforts to get the Count to take him back reveal the Count’s homosexuality and sabotages his wedding to Mina, the society woman he’s stolen from Johnathan Harker.

In the story we actually have, Dracula drinks Renfield’s blood converting him to a blood-obsessed madman. Dracula pursues the women he meets at the opera—first Lucy, then Mina—while trying to present himself as part of the aristocracy. Renfield is torn between trying to warn Dr. Seward of the threat to Mina and his loyalty to Dracula, always suggesting something terrible will happen, but unable to say his master’s name. In the end, while Dracula is taking Mina to his lair to turn her into one of his vampire brides, the heroes show up because they’ve followed Renfield who they find begging the Count to convert him into a vampire instead of Mina.

A queer reading isn’t a stretch because the book itself sees the vampire through a sexual lens. For example, in the novel, Lucy is being courted by three men. She agrees to marry one of them, but all have confessed their love to her. Before she can get married, Dracula begins sneaking into her room and drinking her blood. To keep her from dying, she receives transfusions, first from her fiancé, then her two suitors, then Van Helsing. The fiancé says the initial transfusion was like a consummation of their marriage. The transferal of blood is conflated with a sexual transfer which then sexualizes Dracula’s interactions with his victims.

So it’s interesting to see the first vampiric attack in the movie be not only Dracula drinking Renfield’s blood, but it happens as Dracula’s three brides enter the room and are about to attack Renfield themselves. Dracula chases them off and then descends upon Renfield.1This is one of the differences with the Spanish-language version of the movie. There, Renfield is attacked by the brides, not by Dracula Furthermore, all the scenes of Dracula attacking people are filmed in a way that implies sexual assault. He approaches his victim, starts leaning over the bed, and the movie cuts to black. There’s no blood, no fangs, no, as it were, on-screen penetration. Everything’s implied.

Also, on the note of improper sexuality: Mina’s infatuation with the Count and eventual demand to break off her engagement to Johnathan echo the period’s obsession with virginity. She tries to hide the marks on her neck—the evidence of penetration—and then declares herself unworthy of Johnathan, telling him to leave her moments before she’s overtaken by desire and tries to attack/romance him. In this respect, the anxiety in Dracula, the horror, is improper sexuality: homosexual and female-led. Since horror is often about the restoration of the status quo, naturally this movie ends with Johnathan leaving with Mina after the deaths of Renfield and Dracula. Heterosexuality reaffirmed and saved.

All this despite Harker being a clueless drip throughout the entire movie. He and Van Helsing bumble into Dracula’s lair after they happen to see Renfield sneaking in while they’re walking around for some unexplained reason.2They are coming back from Lucy’s grave where they’ve killed her, finally convincing Harker that there are vampires and that Dracula is one. The Spanish version has the characters say this to each other as they’re leaving the graveyard and then see Renfield. The original, for whatever reason, omits all of that context They don’t even have any equipment with which to attack Dracula; they have to break his coffin lid to fashion a stake and then find a rock. In a sense, the day is saved by their dumb luck.

That’s the nature of horror storytelling at the time, though. The Hayes’ Code, introduced in 1930, demanded that “good” win out no matter what and that could lead to lazy storytelling. What ends up being communicated thematically is that the heroes win because of their inherent qualities—being “good”—but being good is indicated by their adherence to social norms (another Hayes demand). So whiteness, heterosexuality, Christianity, native as opposed to foreign, become markers of goodness even if the movie didn’t intend to send that message. Another unintended consequence is this leads to the villains and monsters being more interesting: there are no character or narrative limitations placed on writing the monsters. The heroes, due to the Code, come pre-written, but the monsters are where the filmmakers get to play. The monsters end up being alluring, sympathetic, more complicated, and thus more compelling than the heroes in most cases.

I’ve gone on quite a bit about a movie I don’t particularly like. I’ve seen it several times and I always forget how boring it is. I cannot overstate how much characters just stand around and talk—both in the book and the movie. Van Helsing is good for some campy pleasure and I’ve already noted my appreciation for both Lugosi and Frye’s performances, but Harker is such a drip. He literally looks like he’s running around in boys’ short pants.

Obviously, the movie is thematically, culturally, and cinematically interesting. Like I said at the top, this is what set everything else in motion and part of what I’ve written here, just like Dracula itself, lays the groundwork for the movies to come. Universal did not have much faith in Dracula (despite splashing out for the film rights) so produced it on the cheap. That’s one reason it doesn’t have a score.3I did see the movie once with the Philip Glass score performed live by Glass and the Kronos Quartet which was pretty neat However, it was a huge success which led to Universal making Frankenstein and, later, The Mummy, The Wolf Man and Creature films. Dracula demonstrated that monster movies have legs. I just wished it wasn’t so staid so much of the time. The Spanish version demonstrates that this did not have to be the case. It’s worth watching for its cultural and historic value, but it’s not very entertaining in and of itself anymore.